Hot on the heels of a magnificent Matthew Passion (Choir of King’s College Cambridge, Academy of Ancient Music, Stephen Cleobury), I found myself on the train back to London, reading the following New Yorker article (March 27, 2017) about the philosopher Daniel Dennett, who studies consciousness. Although the whole article resonated with me, the following in particular struck a chord.

Dennett is often cited as one of the “four horsemen of the New Atheism.” … A few years ago, while he was recovering from his aortic dissection, he wrote an essay called “Thank Goodness,” in which he chastised well-wishers for saying “Thank God.” (He urged them, instead, to thank “goodness,” as embodied by the doctors, nurses, and scientists who were “genuinely responsible for the fact that I am alive.”)

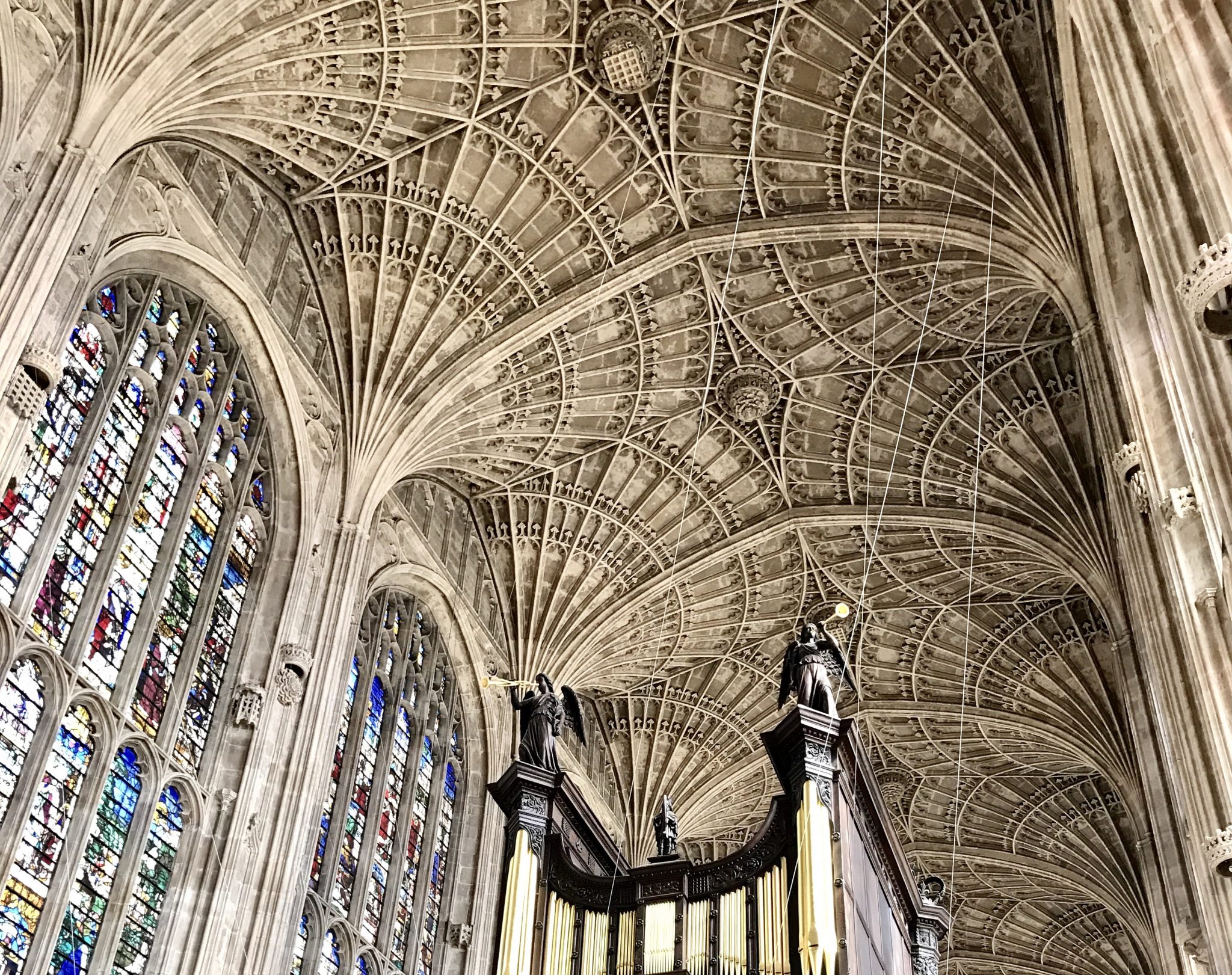

Yet Dennett is also comfortable with religion–even, in some ways, nostalgic for it. Like his wife, he was brought up as a Congregationalist, and although he never believed in God, he enjoyed going to church. For much of his life, Dennett has sung sacred music in choirs (he gets misty-eyed when he recalls singing Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion”). … In a 1995 book called “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea,” he asks, “How long did it take Johann Sebastian Bach to create the ‘St. Matthew Passion’?” Bach, he notes, had to live for forty-two years before he could begin writing it, and he drew on two thousand years of Christianity–indeed, on all of human culture. The subsystems of his mind had been evolving for even longer; creating Homo sapiens, Dennett writes, required “billions of years of irreplaceable design work”–performed not by God, of course, but by natural selection.

“Darwin’s dangerous idea,” Dennett writes, is that Bach’s music, Christianity, human culture, the human mind, and Homo sapiens “all exist as fruits of a single tree, the Tree of Life,” which “created itself, not in a miraculous, instantaneous whoosh, but slowly, slowly.” He asks, “Is this Tree of Life a God one could worship? Pray to? Fear? Probably not.” But, he says, it is “greater than anything any of us will ever conceive of in detail worthy of its detail. … I could not pray to it, but I can stand in affirmation of its magnificence. This world is sacred.”

-Joshua Rothman

St. Matthew always makes me feel this way, too… more committed than ever to my particular brand of atheism, or maybe secular humanism (but not limited to humans)–not a negation of anything, but rather an awe of the extraordinary heights of consciousness, creation, and connection achieved by the human mind and the systems of nature, through a process we are only beginning to understand.